Incarnation: Yao Jui-Chung Solo Exhibition

First conceived in early 2016, Yao Jui-chung's "Incarnation" series covers more than 230 temples, cemeteries, public gardens, and amusement parks, photographed within one and a half years in an intensive manner, featuring the statues of deities created by the Han people by reference to their self-images. Some of these statues are toppled, while others remain standing. Carefully observing these statues, namely the objects of people’s psychological projection, we may further grasp the endemic political relations in different geographical spaces.

The artist evades narrative by intentionally leaving out people in each frame, shunning religious gatherings or festivities. Instead, he focuses on the physical embodiment of the gods — a projection of the devotees’ fervent desire. Adopting a typological approach, he captures not the local folk culture, but the landscape that cradles the staggering sculptures; not unusual cases but mundane existence. Devoid of humans, events, or disasters, this body of work explores the manifestation of human wants in a clinical approach that eschews religious architecture, folk activities, or worship ceremonies. In a dispassionate, monotone palette, this new photography series scrutinizes the inextricable connections between man, religion, and faith.

With few exceptions, all forms of religion equally embody the human desire for happiness, and promise to bring people spiritual growth and salvation, though their approaches may diverge. To attract followers and solidify teachings, symbolic objects or specific images are necessary commodities in addition to scriptures, sermons, incantations, instruments, and rituals. The total of more than 12,000 temples in Taiwan help shape the sui generis temple culture that has become the most enigmatic and eventful dimension of the Greater Chinese world. Most temples serve to address ordinary people’s earthly needs of all stripes, and offer them spiritual sustenance. On a more specific basis, people expect to gain real interests, restore physical health, or satisfy spiritual yearnings for the next life with the assistance of transcendental powers, and the supply-demand issue has ensued. What inspires the followers’ devotion is not their genuine faith in the deities, but the extent as to how efficacious the deities are in producing miracles. And the statues of deities that are larger than life size in every way may well encourage the followers’ devotional practices.

The deities have many different incarnations as statues. Some are as colossal as buildings, others are medium in scale and several meters high, still others are small statues enshrined in the main halls of temples or on household altars. If we compare a colossal statue of deity to a supercomputer, small statues would be laptops. A computer wields no magic power if it is disconnected from the server. The consecration is to a statue what the password is to logging onto a computer. To be efficacious, the incarnations must connect themselves with the host deity. The increase of a deity’s supernatural power bears comparison with the upgrading of a computer’s software. The position of a temple keeper closely resembles that of a computer engineer if we construe a temple as an omnipotent computer. The temple keeper helps the followers solve particular difficulties, while the engineer protects the computer from virus attacks. Once a deity leaves a statue, which is nothing short of removing a computer’s CPU, the statue would no longer be the embodiment of human desires but a mere shell to be decomposed over the course of time.

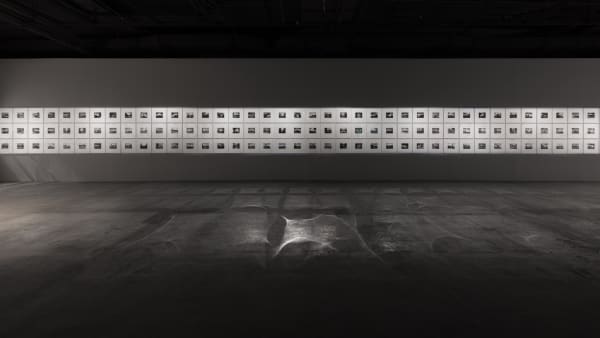

The desires of the multitudes shape the explicit forms of these colossal statues of deities. However, these materialized forms are every bit as illusory as dreams and bubbles, since emptiness is the nature of tattva, or ultimate reality. Yao Jui-chung captures the absurdity of deity statues against the urban backdrop, where the interconnecting relationships between deities and humans resonate to the mundane desires that are at once vacant and lusty. Distilling a sense of beauty in the monotone palette, the 300 images document the sensualist society with clinical detachment.

In addition to the array of 300 gelatin silver prints that portray the human desire, a three-channel video installation of Incarnation is also on view, where the rising and falling tones of the complex radio spectrum of Saturn recorded by NASA transport the viewer to the mystical universe. Deities of all stripes on the three screens instantiate the intertwining relationship between history and society. Evoking a road movie, the video installation deconstructs and repaints the landscape of Taiwan, suffused with a magical divinity interspersed with sentient yearnings.

There is also a performance by sound artist Dawang Yingfan Huang and musician Meuko! Meuko!, who is known in Japan and Taiwan for her experimental approach to electronic music. Conceived as a modern version of religious tribute to the gods, the collaboration reassembles the visual and sound elements of a traditional temple fair and conjures an organic performance that manifests Taiwanese cultural and religious beliefs.

Yao Jui-chung

Born in Taipei in 1969, Yao Jui-chung has exhibited extensively, including at the Sydney Biennale (2016), Venice Architecture Biennale (2014), Asia Triennial Manchester (2014), Asia Pacific Triennial (2009), Yokohama Triennale (2005), and Venice Biennale (Taiwan Pavilion, 1997). Awards and recognitions include the Asia Pacific Breweries Foundation Signature Art Prize (Singapore, 2014) and Multitude Art Prize (Hong Kong, 2013).

The artist is engaged in a diverse range of mediums such as painting, installation, and photography, while photography remains his main artistic language. His seminal work includes the "Action Series" (1994–2002), which examines Taiwanese subjectivity, postcolonialism, and Chinese modern history and politics; "Phantom of History Series" (2007), which mocks authoritarianism; as well as Long Live (2011) and Long Long Live (2013), which ponder the lasting influences of the White Terror and Martial Law period. In addition, he combines photography with installation in Barbarians Celestine (2000), which emanates an air of hypocrisy and alienation that is specific to Taiwan.

Continuing his examination of the irredeemable absurdity in human history, the artist compiled in 2005 a series of images he took over a decade around Taiwan that coalesce into a grand picture of Taiwanese ideology shaped by globalization and the island's unique history. This led to "Mirage: Disused Public Property in Taiwan"(2010–2016), a project that galvanized public opinion and indirectly provoked government action by documenting in black-and-white photography the infamous "mosquito houses," or extravagant public spaces supported by government funding that have been left idle. The artist's latest series "Incarnation" (2016–2017) delves into the Buddhist notion of endless reincarnation, and examines the curious spectacle of Taiwanese religious beliefs manifested through colossal deity statues.