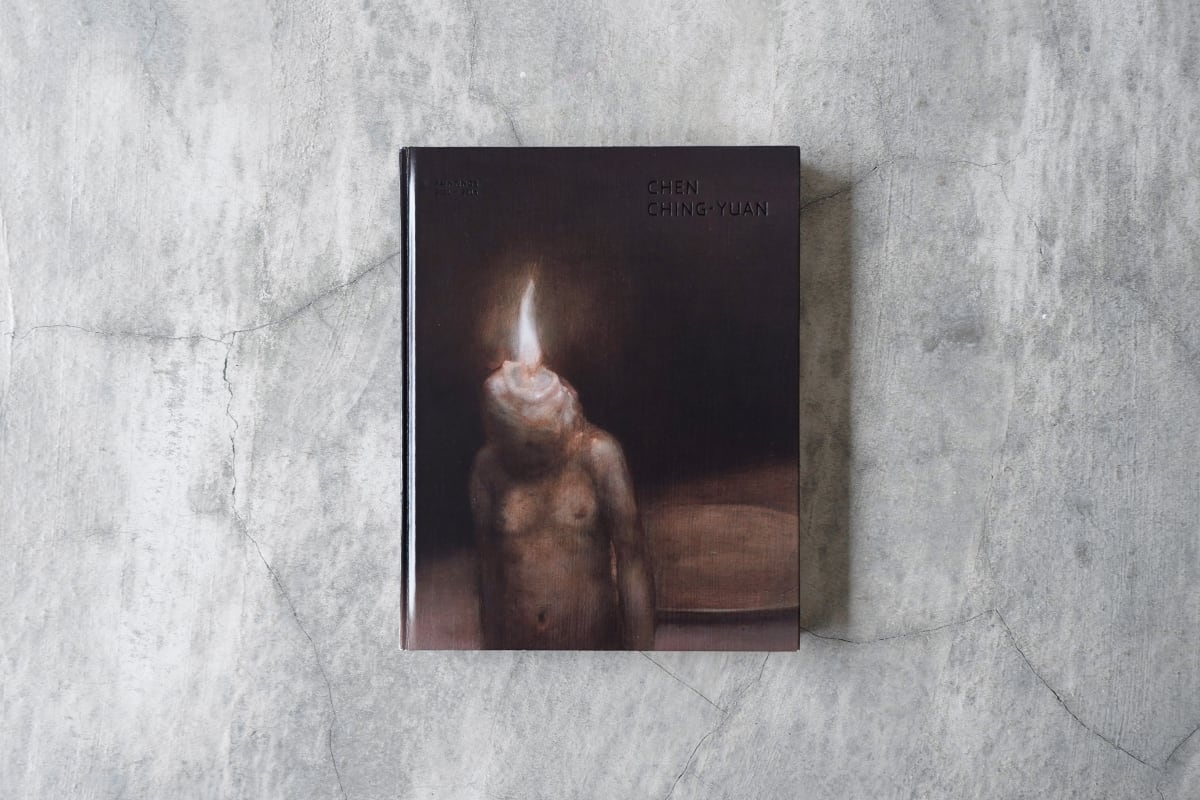

What am I? If I can’t be yours: Chen Ching-Yuan Solo Exhibition

In recent years, Chen Ching-Yuan has tended toward a neo-classical ambiance in his painting, partly as a conscious reduction of the explosive quantities of information in his previous body of work, and partly as an elevated attentiveness to the aesthetic elements in artistic creations. Narratives, perceptions, and symbols are consistently fragmented in his oil paintings, transforming his work from “information” into “perception” as it enters a bigger picture of his overall art practice. But what is the reason for these perceptions? We must pay attention to the fact that in contemporary art, shared experiences of daily life do not provide easy clues to reality. To a certain extent, a framework with rationality and concepts as its guiding criteria hinders observation and undermines the prioritization of aesthetic attributes. The work becomes objectified, while the shared language between the viewer and the artist becomes increasingly alienating. The viewer stands gazing at a work awaiting an artistry that grows more distant, and the ability to extract aesthetic elements as an object of perception is incrementally lost. This is just as Chen Ching-Yuan mentions offhandedly in conversation, “Actually, I feel as though art making is more like curating these days.” Herein lies the problem. If this fragmented production becomes incapable of regenerating structures or of regenerating itself, then everything within it becomes materials supplementary to the subject. How does the self operate within a space whose boundaries are slowly attenuated when the fragmented subject is supplemented by a profusion of objects? This not only concerns modes of art production, but also unconsciously influences the viewing experience. This condition often strengthens the familiar yet distanced endpoints of the individual viewing experience as it confronts the relationship between art and the real world as mediated by capitalist logic, inducing the viewer to hover between the fictional and the real.

First, in reference to Chen Ching-Yuan’s creative context to date, his acrylic paintings prior to 2011 actively applied a plethora of representative symbols linked to social issues, with the intention of re-presenting the information explosion in his creative contemplation. This contemplation, with an emphasis on iconography, is characterized by its clandestine presence as a form of information in the context of political consumption, in a direct and stark self-expression as a response to society. Here, the creative mode often takes the form of a singular work that is a complete expression of his thoughts, declaring the same statement by using the same words over and over again. In his 2011 solo exhibition Staggering Matter, the self of the artist displayed through his prolific use of mixed media, video installations, and paintings could be seen as a pause from his iconographical thinking. What he pauses to contemplate is a certain self-dialectic, a dismantling of the self where he removes the subject from the external reality and connects it directly to the digestion of information. It is solely through the varying mediums that he fine-tunes the relationship between the works. In turn, his holistic oeuvre can no longer be gleaned from a single work. The fragments of thought can only be pieced together from the fragile introductory text to the exhibition. But it is easy to discern how the painting James (2011), with its airs of neoclassicism, leaves clues to his painting practice to come.

The turning point in his art practice can be traced back to the “Sunflower Movement” [2] that took place in 2014. On a social issue where reality clashed with imagination, where the societal participation of art on the scene of the protest required a high degree of dynamism and quick response capabilities, many young artists fell prey to self-doubt and feelings of powerlessness under the immense pressure of realism. Chen Ching-Yuan was no exception. His practice of “painting from life on the legislative floor” elicited discussion and criticism on issues of artists’ political participation. In his position as an artist, Chen Ching-Yuan’s entry into a social movement and into the front lines of the allocation of political power was an intention to understand the realities and conditions of art within social operation, to confirm how the self fits into the grand picture. It was never a means of self-redemption or a burden of imagination, but rather an issue of re-presentation in his creative practice that the artist immediately confronted. Except in the media-saturated present, this “realism” is perhaps more akin to a certain “meta-realism.” In this world, the consumption of information has become an aim, a catalyst for a self-reproduction of images resulting in the negation of meaning rather than the transmission of information. As a result, in this highly assimilated aggregate, one’s subjective self is translocated to the fragmented objective self focused on culture, symbolism, and language, where the internal and external are undifferentiated. This experience of meta-realism does not follow realist principles of re-presentation in the past, but exists as a dialectical aesthetics of simulacra that oscillates between the reversibility of time, the fragmented subjective self, and the ambiguous objective self. It is an unnamable language with the ability to transform ways in which the real world is observed. The painting and works that came into being on the legislative floor remained sealed in memory, but the further confirmation of the relationship between the artist and society through the bodily participation, juxtaposed against the violence and reality in the contested exercise of power, becomes a sort of mutual probing that ultimately leads to an internalized, perceptive realm of art.

A careful combing through Chen Ching-Yuan’s creative trajectory and processes intends to re-contemplate his thoughts on confronting society through the specificity of images in his work. This also reflects the difficulty in interpretation, and the overpowering visual “aesthesia” present in Chen Ching-Yuan’s oil paintings post-2013. The complexity of comprehending structures of reality makes it impossible to speak in absolutes about his work. Most of this ambiguity comes from an understanding that the struggles with reality are rarely simply about rights and wrongs, but are rather an access to an operational reality that further reveals ways in which contemporaneity affects one’s thoughts and perceptions. Here, his paintings harmonize and balance the real world. This realness does not merely exist in a shared reality; clues can also be found in the world constructed through his paintings. Chen Ching-Yuan once described his own work thus, “I feel as though my work is a sampling of reality. No matter what I do, it is merely a fragment. But through these fragments I hope to present a certain regularity and destiny, an inescapable operation. My paintings are like objects salvaged from a lake. They are reflections on my experience of realities, and some choices must be made.” Using this as a point of entry, we could perhaps temporarily set aside the interpretations provided by the external image of his paintings (attributes reminiscent of neoclassicism such as the hues, religiosity, and politics), and turn our gaze toward the creative thinking of the artist.

… This object is me, the figure which forms me. This is the me that can be seen, yet I feel as though I am not myself. Very strange. I feel as if my body is melting. I can no longer see myself. My shape is fading. I feel the presence of someone who is not me. Is someone there, beyond this? ...

— Rei Ayanami, Evangelion, Episode 14

The appeal of Chen Ching-Yuan’s paintings lies in a temporary reality created through the fragmentation of the subjective self in the name of creativity. It is an evocation and a structural compulsion, as well as a foundation for constructing this air of meta-realism. As the subjective self cannot be fully presented, there will be stumbling blocks in readings of individual works. Part of this fragmentation can be replenished by elements of fantasy, but these replenishments will never equal the original subjective self. In this context, a shattering of subjectivity and the temporal dimension allows the objects within the work to be retained. It is a gap that perpetually accepts projection, while simultaneously highlighting an escape of the subjective self and a structural rigidity in contemporary society when the subjective self is no longer tethered to reality. The paintings in his 2016 solo exhibition, What am I? If I can’t be yours, appropriate projections of a fragmented subjective self, a differentiation of the image experience, and a re-recognition of the self that shapes self-identification, in order to replenish the creative subjective self. On canvas, the self-perception in each work is at times emphasized, and at times with information deliberately omitted through a number of deliberate internalized choices in the painting. An intensive use of color in parts and a loose composition in others ensures an absence of linear connectivity between paintings; neither does a specific expression exist in the works on a collective whole. Instead, these numerous fragments that bear witness respond to a sense of regularity and destiny as they enter a non-representative world. Here, differences cannot be discerned. When familiar but unrecognizable symbols appear within the work, they are not related to anything in the external reality but are dependent solely on a closed ego-structure system. The artistic choices he has made, of which he is conscious, and the creative subjective self evoked therein, are no longer individual works linked through a narrative structure, but part of a larger Other that constructs a creative perception in the name of the exhibition.

The reality that What am I? If I can’t be yours leads to is a mode of operation that is rendered abnormal as a result of dismantling reality. To paraphrase the French philosopher Baudrillard, only in the reflection of the mirror can the subject become alienated from himself in order to rediscover himself; or through a seductive and lethal other which allows the subject to rediscover himself through his own demise. Here, creativity is a behavior that reconstructs the thinking and perception of the subjective self. Ultimately, we see that through his paintings Chen Ching-Yuan has made perceptual adjustments to the real world, in another world evoked by the temporary reality of the exhibition. In the same vein that these words are not an interpretation of Chen Ching-Yuan’s solo exhibition, the mode of operation thus produced is only a path that leads to a contemplation and perception of Chen Ching-Yuan’s world of painting. This open-ended conclusion is but a method, and not a definitive statement of the exhibition.