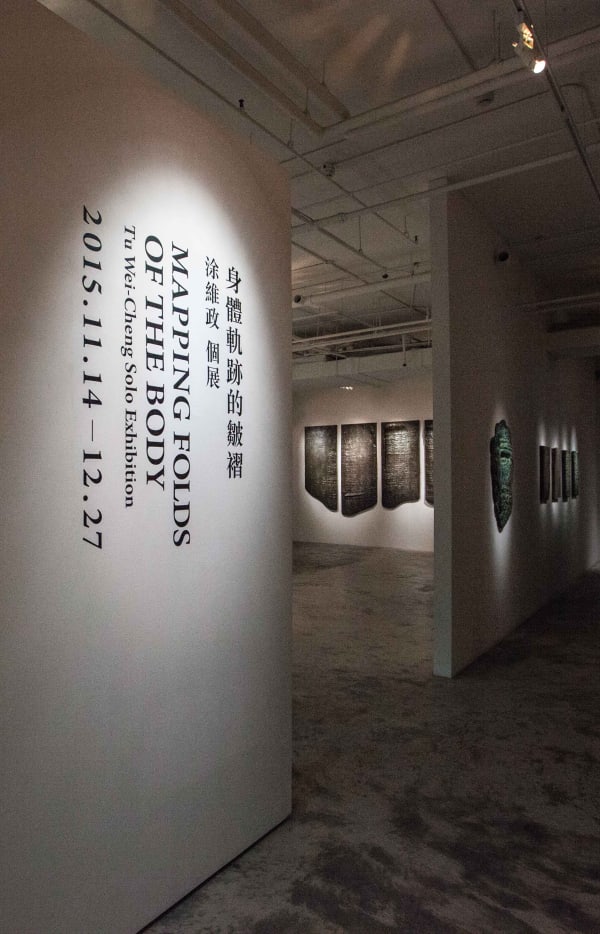

Mapping Folds of the Body: Tu Wei-cheng Solo Exhibition

Existing between contemporary living and archival history, ambiguous conflicts morph into seemingly multifaceted, yet in fact unilateral solutions to issues arising in complex political power play, unequal economic distribution, and shifting subject awareness. It is against this backdrop that the question of truth seems to have become ridiculously rhetorical.

Tu Wei-cheng (b. 1969) centers his multidisciplinary art practice on a search for singularities between life and history. He is adept at creating a personal play of the absurd, where by leaving behind mysteries waiting to be solved through witty banter with the viewer, he acknowledges his uncertainty and doubt about the world's structure and questions his place within. In the "Confucius Series" (1999) and You’re a leader, too(1999-2010), the artist ridicules the image system prevalent in education and state mechanism in the form of composite imagery, while he deludingly changes viewers’ perception in a cunning orchestration of forgery and replication in Bu Nam Civilization(2003) and Ancient Art Hall Auction(2004). Ostensibly failed attempts to uncover truth through faux archaeological excavation lead solely to stringent doctrine, triggering a series of discussions on value and meaning. In his 2015 solo exhibition, Tu explores an element that weaves through his art practice but has long been ignored — the connection between the body and the work. As a continuation of Bu Nam Civilization(2003), the exhibition looks back on physical activity as a catalyst in Tu’s art practice through which he documents the dynamics of his work as well as his personal reflections.

In Mapping Folds of the Body, the artist works with everyday objects such as toys, tools, painting frames, disassembled fitness equipment, even electronic or industrial waste to produce large engraved cylinder seals, similar to those from ancient Mesopotamia that were used to document significant events. Repeatedly the artist rolls these large cylinder seals along to create impressions on modeling clay; the results are bas-reliefs that defy boundaries of image and text. The traces and marks left behind by the weight of the artist’s physical being during this process reflect the connection between the body and the exterior world in the practice of art. Together these authentic objects born out of the artist’s manual labor, which imitate their Mesopotamian counterparts, outline an individualized civilization, where familiar yet foreign imagery attests obscurities that characterize contemporary living.