The King and I: Mit Jai Inn Solo Exhibition

Dates

05 DECEMBER 2020 - 30 JANUARY 2021

Reception

05 DECEMBER, 4:30 p.m.

TKG+ 1F, No. 15, Ln. 548, Ruiguang Rd., Neihu Dist., Taipei 11492, Taiwan

Born in 1960, Mit Jai Inn grew up in Thailand during the Cold War period. In addition to his own participation in cultural politics, the artist has shaped his practice around history, politics, and public issues. With abstract art lying at its core, the form and presentation of his work defies convention. He is considered one of the forerunners on the Thai contemporary art scene. His latest body of work made in 2020 echoes recent political protests in Thailand. As the ongoing student movement intensifies, Mit not only participates in the protests himself, but also instills a clear political statement in his work and exhibition.

Thailand’s constitution stipulates that the Thai royal family should stay above politics and remain politically neutral. King Rama X, or Maha Vajiralongkorn, who ascended to the throne in 2016, consolidated the power of the royal family and the military through constitutional amendments several times, during the term of Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha, who rose to power after the 2014 coup. King Rama X even promulgated a new law that gives the King direct control of tens of billions of assets of the royal family, not to mention the absurdly extravagant lifestyle that has frequently captured the attention of international media. "The King and I," the title of Mit’s solo exhibition at TKG+, reverberates with a dark sense of humor that evokes the famous American drama with the same title, which has been banned in Thailand for years[1], while instantiating the artist’s call for royal reform.

Thailand has been a constitutional monarchy since the overthrow of absolute monarchy in 1932. Though the only uncolonized country in Southeast Asia, Thailand has felt the profound influence of the Cold War on its modern politics, suffering from prevalent military interventions. The Thai political landscape has been on a precarious balance of terror among the royal family, military power, and political elite, who together witness the October 6 1976 massacre[2], as well as three major military coups in 1991, 2006, and 2014[3]. Thailand’s democratic system and military dictatorship are in a constant tug of war. The military also maintains its advantage in the democratic system through constitutional amendments and censorship of speech. The Future Forward Party, which became the third biggest party in the parliament in the 2019 Thai general election merely one year after its inception, won the hearts of young Thai people with its advocacy of military withdrawal from politics and of a more equal economy. In February 2020, the party was ordered by the constitutional court to dissolve over a controversy.[4] This became the onset of an ongoing student movement, and exiled dissidents were arrested. The Free Youth Movement initiated street protests in July, joined by the Milk Tea Alliance[5], which saw the number of participants grow from 3,000 to tens of thousands in a month, drawing the attention of international media.

The economic issues that have weighed on Thailand include wealth gap widening in its M-shaped society, population growing below poverty line, discontent and despair of young generations with class difference and the future. In contrast to Thai people’s worsening economic state, the complete control of the royal estate and political interference of the Thai King, as well as the Prayuth government’s dictatorship, have fomented civilian outrage. Just like Michel Foucault’s interpretation of Jeremy Bentham's panopticon, Thailand's political technology and power mechanisms continue to be strengthened by the changing laws made by those in power, against a backdrop where the elders and the powerful are respected and obeyed, while Thai people live in extreme political repression on the fringe of the democratic system.

Upon his return to Thailand from Austria in 1992, Mit cofounded Chiang Mai Social Installation with a group of artists, scholars, and social activists. Together they debuted a project titled Magic Set Visual at the Dhamma Gallery Three months before a massacre took place in May 1992. Ever since then, this group has continued to share their political opinion through cultural forces, art making, and exhibitions that champion protests, as well as joining activist groups in street demonstrations. One of Mit’s ongoing series that supports such cause include the "Siam Republic Flag," which was conceived in 2010. In fact, Mit never acknowledges the existence of the kingdom, nor does he believe that the Thai King deserves such respect, or that the people should be jailed for violation of the royal defamation law if they are not discreet with their words and actions. While most Thai people lead their usual lives, and royalist protests take place to support the King, the ongoing anti-monarchist protests in Thailand are unprecedented in recent Thai history. In addition to a constitutional amendment proposal and a demand for Prime Minister Prayuth to step down, the biggest difference from the past is the cry for reform in the royal family. The unwavering status of the royal family in Thailand’s collective state consciousness makes it dangerously difficult to challenge, as the royal family, religion, and politics have become a closely interwoven trinity. On a deeper level, this is a war between two generations: young people and reformers vs. vested interests and conservatives. It is also a grassroots movement in which a large number of middle school students have participated in the appeal for peace. For Mit, the young generation of today are the victims of past political climate. He cannot stand by and watch the corruption and abuse of power of the royal family. Despite the stringent censorship of the autarchic government, Mit thinks it’s imperative to voice his opinion through action and his work, to expose the dark side of the royal family, to stand with the students at this critical juncture.

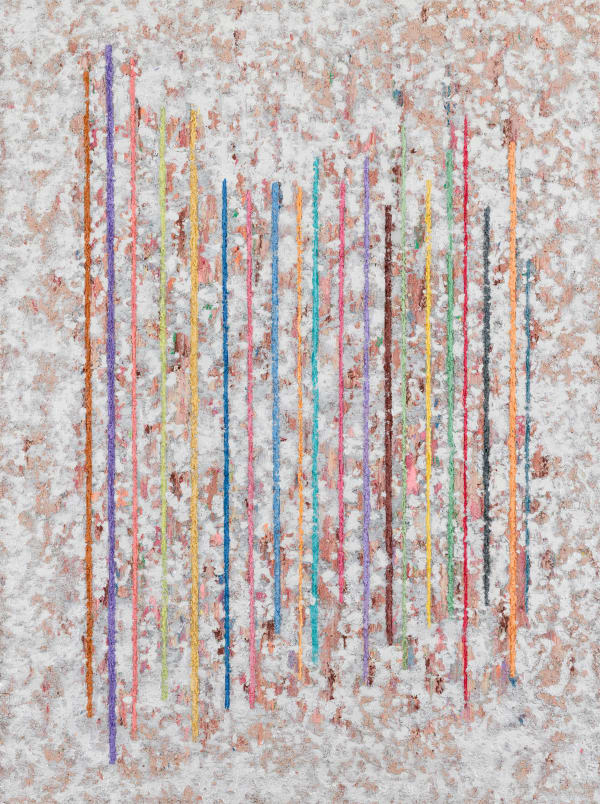

For Mit’s solo exhibition The King and I, the metallic tone is inspired by mummification in ancient royal families of different countries. The artist overlays his sculptures and paintings with gold and silver metallic paint, as if embalming each work like a human body. He made a substantial amount of sculptures in 2020. On an elemental level, the artist’s body transforms through historical and conceptual analysis into a sculpture, upon which a coat of paint over a piece of canvas mimics the skin. In the "Neuron" series, metal as the primary medium of the sculptural works remains malleable, allowing each work to stand on its own as a living organism, coming alive when suspended, depleted and drained when left on the ground. Art making, for Mit, is a sublimation of bodily perception, propelled by emotions, a process where each step must be completed. Just as in the "Psychedelic" series, the scraped lines, the textured paint, indescribable details coalescing into a spirituality. The series is characterized by especially bright, artificial, and unnatural tones that invoke a dreamy, heavenly atmosphere, as well as the hippie culture of the 1970s and New Age of the 1990s. Much like the impressionist’s visual reaction to classicism, this series transports the viewer to an impossible utopia on an escapade from reality and capitalism. Constantly walking the line between painting and sculpture, Mit creates sculpturesque paintings with mixed media, and painterly sculptures interwoven with paint-splattered canvas. The metallic and psychedelic tones encapsulate the artist’s "tribute" to the Thai royal family, while his profound concerns for Thailand’s future mingle with his work.

About Mit Jai Inn

Mit Jai Inn studied art at the Silpakorn University from 1983 to 1986, and at the University of Applied Arts Vienna from 1988 to 1992. He has exhibited internationally, including The King and I, TKG+, Taipei, Taiwan (2020); Sunshower: Contemporary Art From Southeast Asia 1980s to Now, Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts, Kaohsiung, Taiwan (2019); Light, Dark, Other, TKG+, Taipei, Taiwan (2018); 21st Biennale of Sydney, Cockatoo Island, Australia (2018); Sunshower: Contemporary Art From Southeast Asia 1980s to Now, Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan (2018); Medium at Large, Singapore Art Museum, Singapore (2014); All Our Relations, 18th Biennale of Sydney, Sydney, Australia (2012); Tropical Nights —Lost in Paradise, Palais de Tokyo, Paris, France (2007); Dong-Na, Singapore Biennale, Singapore (2007); Soi Project, Yokohama Triennale, Yokohama, Japan (2005); Chiang Mai Social Installation, Chiang Mai, Thailand (1992–1996).

[1] American drama The King and I is an adaptation of Margaret Landon’s 1944 novel Anna and the King of Siam, which was first adapted into a musical, later as an eponymous film.

[2] On October 5 and 6, 1976, students who had gathered at the Thammasat University in Bangkok to protest the return of military dictator Thanom Kittikachorn from exile were brutally assaulted, sexually abused, and beaten to death. This incident put an end to the short-lived democratic period that had began after the 1973 Thai popular uprising, and led to the implementation of martial law under a military government.

[3] In 1991, the Royal Thai Army staged a coup that overthrew the government of Chatchai Chunhawan; it also suppressed a peaceful protest in 1992 in Bangkok by opening fire on demonstrators. In 2005, the Thai Rak Thai Party led by Thaksin Shinawatra won the election, and the "Yellow Shirts" led by opposition party People's Alliance for Democracy took to the streets to demonstrate, triggering a military coup in 2006 that drove Thaksin into exile overseas, and the disbanding of his party. A decade-long political feud was then instigated by the "Red Shirts" led by the United Front of Democracy Against Dictatorship, which supported Thaksin, and initiated several large-scale street protests over the years. In 2014, Prayuth Chan-ocha, commander-in-chief of the Royal Thai Army, organized a coup that helped him take control of the government, and he later imposed martial law. There has been a total of 12 military coups since 1932 in Thailand.

[4] Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit, leader of the Future Forward Party, provided a loan of 191 million baht to the political party. The Constitutional Court of Thailand dissolved the political party, and forbade Thanathon to engage in politics for 10 years. The controversy lies in that while Thailand’s political party law stipulates that the source of income of political parties does not include loans, it does not prohibit loans, either.

[5] Formed in April 2020, the Milk Tea Alliance is an online democratic solidarity movement made up of netizens from Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Thailand. It originally started as a response to the increased presence of Chinese Communist ideology on social media. Later joined by netizens from other countries in Asia, it has evolved into a cross-national movement against totalitarian rule.

VIEWING ROOM